Anne Frank, a Jewish girl, was forced into hiding with her family during World War II to escape the Nazis. With 7 other people she hid in a “secret annex” in her father’s former place of business in Amsterdam. After over 2 years in hiding, all 8 were discovered and deported to concentration camps. Anne’s father, Otto Frank, is the only one of the 8 to survive. Anne died at the age of 15 in 1945 at Bergen-Belsen. We know of her story from her careful, insightful diary, which was recovered from the annex after the arrest.

Dr. Albert Schweitzer was born in 1875 in Alsace-Lorraine (then, a part of Germany). Although today, somewhat forgotten and, even controversial, in the mid-20th Century, Albert Schweitzer’s was a name that instantly evoked images of heroism, selflessness, and humanity. Growing up, I remember my admiration for Schweitzer, who gave up a world-recognized career as an organist and scholar to study medicine and to found a hospital at Lambarene, situated in what was then known as French Equatorial Africa. His vision, determination, courage, and self-sacrifice inspired world-wide recognition and a Nobel Peace Prize. Today, our view of Schweitzer has been overshadowed by some of his statements which are tainted by colonialism, paternalism, and racism, countering his avowed “reverence for life.”

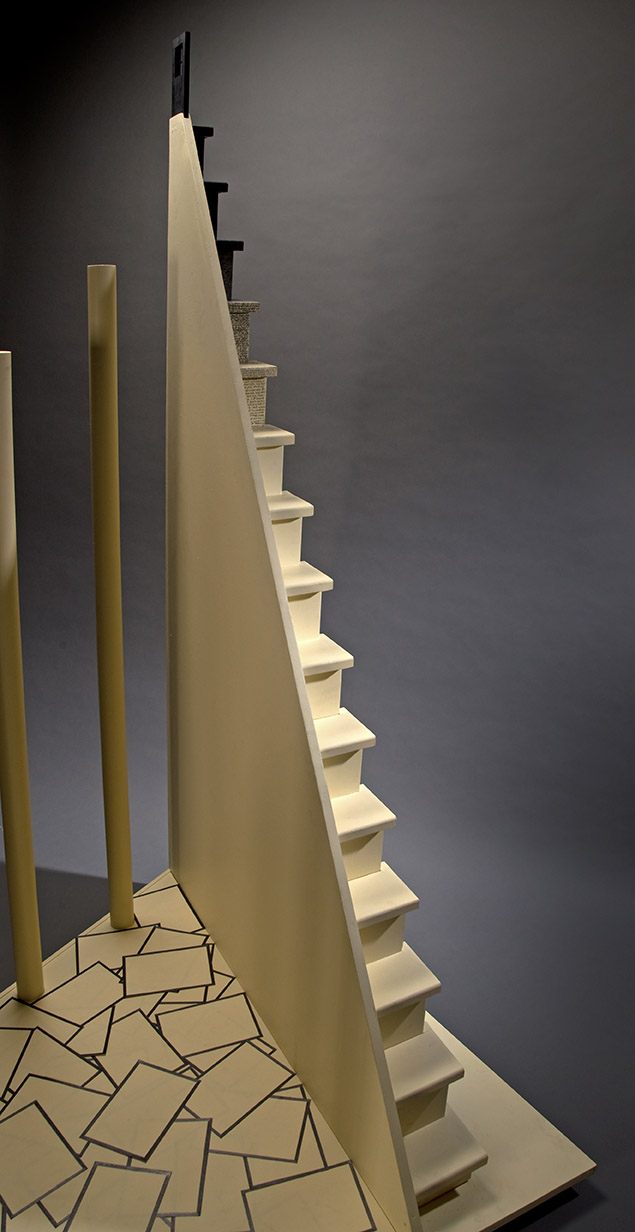

The meeting between Anne Frank and Albert Schweitzer includes 99 drawings. The 9 drawings on Anne’s side consist of graphite rectangles. These are arranged much like the photos Anne arranged on the walls of her tiny sleeping quarters in the “secret annex.” On Albert Schweitzer’s portion of the tableau, 90 identical “pages” have graphite borders and are strewn about the floor, like leaves beneath tropical trees.

In the sculpture, Anne Frank and Albert Schweitzer play “Hide and Seek,” but, in this tableau, it is Anne who seeks and Albert who hides. At the pinnacle of the piece, Anne’s tiny window looks out onto the world. Ironically, Schweitzer’s work is essentially hidden from her vantage.